The Alcan Highway: The Engineering Marvel of World War II

- djonzim

- Jun 10, 2023

- 3 min read

“The biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal.”

—Major Robert W. Madden

On January 20, 1943, at the opening session of the annual meeting of the American Society of Civil Engineers in New York City, high-ranking officers of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and officials from the Public Roads Administration told a rapt audience of their experience building what the New York Times described as “one of the wonders of the modern world,” the Alaska-Canadian Highway, popularly known as the Alcan Highway.

Proposals for such a road had existed since the 1920s, but little was done until Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Immediately defense of remote Alaska became a priority. Plans for the Alcan Highway, a strategically secure supply route, accelerated under the aegis of the Army Corps of Engineers.

In February 1942, just two days after he had received the assignment, Assistant Chief of Engineers Brigadier General Clarence L. Sturdevant, the “Father of the Alcan Highway,” submitted a plan for surveys and construction. In it he specified, “A pioneer road is to be pushed to completion with all speed within the physical capacity of the troops. The objective is to complete the entire route at the earliest practicable date to a standard sufficient only for the supply of troops engaged on the work. Further refinements will be undertaken only if additional time is available.” His target completion timetable: fall 1942. Many called such a feat impossible. The highway’s route went through rugged, unmapped wilderness and would have to be built under some of the most extreme weather and topographical conditions imaginable. But the operable phrases were “pioneer road” and “a standard sufficient only for the supply of troops.” Basically the Army engineers would blaze the road and make it suitable enough for military purposes. The Public Roads Administration was responsible for follow up improvements to make it capable of handling civilian traffic.

A crane working on the Alcan Highway.

Surveying began in February. Using locals as guides and constantly updated aerial photos, survey teams averaged two to four miles a day. Once the basic route was worked out, seven engineer construction regiments were prepositioned at points along the route and each was responsible for constructing a 350-mile section of the road. Three of the regiments, the 93rd, 95th, and 97th, were African-American regiments and Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., responsible for Alaska’s defense, initially tried to bar them from his area of operations.

This was the era of Jim Crow and a segregated Army. Buckner was also the son of a Confederate general. Buckner’s objections were racist; his concerns dwelt on the possibility of miscegenation between the African Americans and native peoples, not competency. Two of the three African American regiments, the 93rd and 97th, were sent to Alaska. To alleviate Buckner’s concerns, they were stationed far from any settlement.

Construction of “The Road,” as it came to be known, began on March 8, 1942, and the person responsible for the actual building of the highway was Brigadier General William M. Hoge, creator of the obstacle course. Hoge quickly discovered that when it came to building a road in this remote northern wilderness he had to unlearn almost everything he knew. The primary reasons for that were muskeg, bogs of rotten organic matter and muck, and permafrost, permanently frozen ground. Traditionally, trees and other vegetation and topsoil are bulldozed away to make a level foundation for the road. Hoge recalled, “That was absolutely wrong with permafrost . . . you had to do exactly the reverse.” Instead, teams had to fashion layers of felled trees and other vegetation over the permafrost and muskeg to create an insulating blanket to prevent them from melting. Once a firm surface was in place then a road could be built.

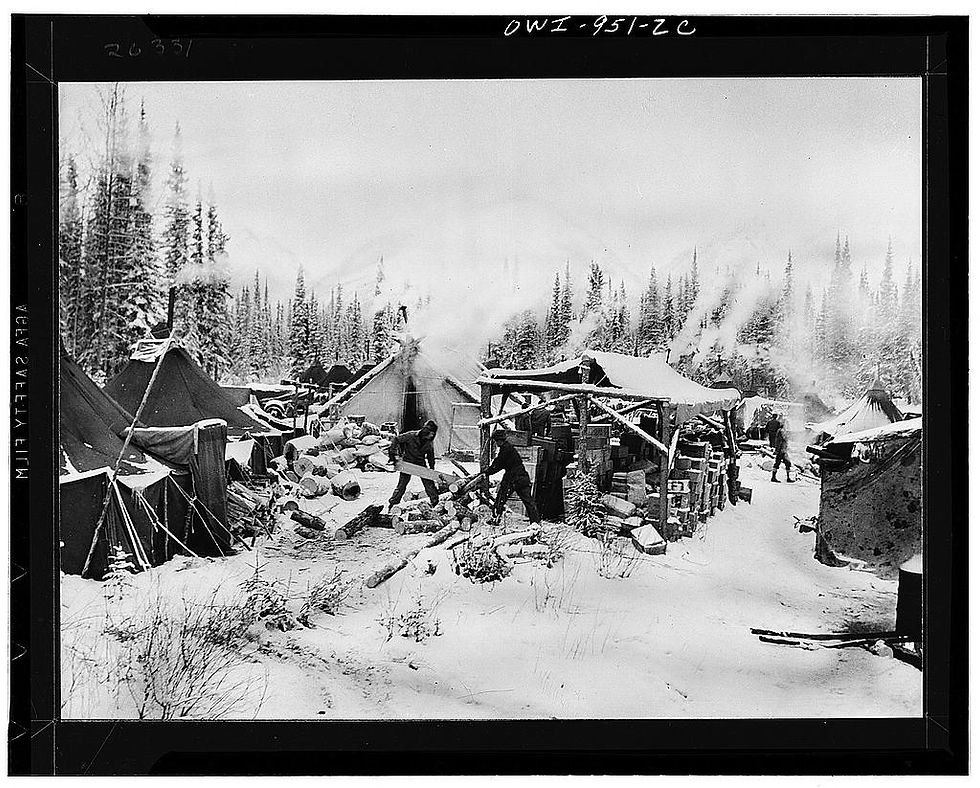

A sawmill used to help build the Alcan Highway. Note the winter conditions.

The troops also worked in extreme weather conditions, with winter temperatures reaching –70 degrees Fahrenheit. “The worst I ever saw,” Hoge recalled. Mosquitos and other bugs were also a huge problem. When eating, Hoge said, “. . . you would raise [your mosquito] net and by the time you got food on the spoon up to your mouth it would be covered with mosquitos. You were eating mosquitos half the time. . . .” And when the men weren’t eating mosquitoes, the insects were eating them. Hoge said, “I’d put my hand on my neck and [would] pull it back and it would be covered with blood from my neck.”

When it was completed on October 28, 1942, 1,700 miles of road, from Dawson Creek, British Columbia to Delta Junction, Alaska—the first all-weather route from the continental United States to Alaska—had been built. By then the strategic need for the highway had passed, nonetheless the Alcan Highway was hailed as one of the top ten construction achievements in the twentieth century, and is still in use today.

Some of the spectacular scenery along the Alcan Highway.

Comments